Everyone knows that going to the gym, running, or doing yoga is good for our bodies. We see the results in toned bodies, better endurance, and maybe even a lower number on the scale. But what if I told you that the changes that will last the longest are happening in your head, which is less obvious but much more complex? Yes, we’re going to talk about how working out can make your brain healthier in a big way. It’s a fascinating journey that goes far beyond building biceps. It shows how moving our bodies affects our memory, sharpens our focus, and even makes new brain cells. Don’t think of exercise as just a way to stay in shape; it’s one of the best ways to boost your mental health.

For a long time, people thought that the brain was a pretty stable organ that grew up through childhood and then slowly got worse with age. But neuroscience has proven this idea wrong with the idea of neuroplasticity, which is the brain’s amazing ability to change itself, make new neural pathways, and rewire itself over the course of a person’s life. And guess what? Exercise has a strong effect on all of this good rewiring. It’s not just about how good you feel because of endorphins; every time you exercise, your brain changes in real, structural, and functional ways.

In this article, we’ll look at the complicated link between exercise and how the brain works. We’ll look at how different types of exercise, like aerobic exercise, strength training, and yoga/mind-body exercises, help improve memory, concentration, and the amazing process of neurogenesis, which is the creation of new brain cells. Get ready to learn how your workout routine is doing more for your brain than you ever thought possible.

The Brain-Body Connection: More Than Muscle Fuel

Let’s learn how exercise affects the brain before we dive into the exercises themselves. It’s a complex process:

1. Increased Blood Flow: Your heart beats faster when you exercise, pumping more blood through your body, including your brain, which is ravenous for resources, using up to 20% of the oxygen and energy of your body. Increased blood flow provides an important supply of oxygen and glucose, the brain cells’ main fuel. It also facilitates the removal of metabolic waste products more effectively. Imagine upgrading the delivery system to your brain headquarters – quicker, more efficient, and better armed.

2. The Chemical Cocktail: Exercise releases a potent blend of neurochemicals:

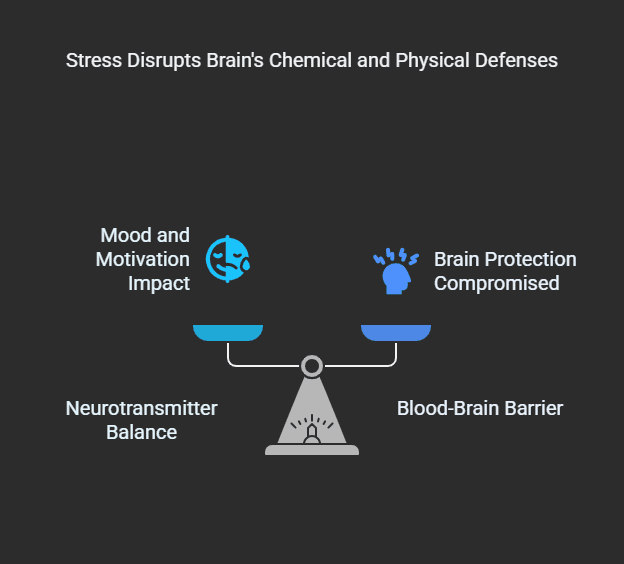

- Endorphins: Renowned for the “runner’s high,” these are natural mood elevators and painkillers.

- Dopamine: Essential in motivation, reward, learning, and attention. Exercise will frequently result in a surge of dopamine, creating feelings of accomplishment and concentration.

- Serotonin: Regulates mood, sleep, and appetite. Regular exercise can balance serotonin levels, a move that may ease symptoms of depression and anxiety.

- Norepinephrine: Plays a role in alertness, attention, and the stress response. Exercise regulates its release, enhancing focus and resilience.

- Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF): It’s a star player in brain rewiring. BDNF is fertilizer for your neurons. It helps existing neurons survive, promotes the growth of new ones (neurogenesis), and helps form new connections (synaptogenesis). We’ll discuss much more about BDNF.

- Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1): Secreted in the muscles and liver during exercise, IGF-1 makes its way to the brain and acts in conjunction with BDNF to stimulate neuronal growth, survival, and plasticity.

3. Decreased Inflammation: Chronic inflammation is bad for overall health, including brain health. It’s associated with cognitive decline and neurodegenerative disease. Regular moderate exercise has anti-inflammatory properties, protecting the brain from this damage.

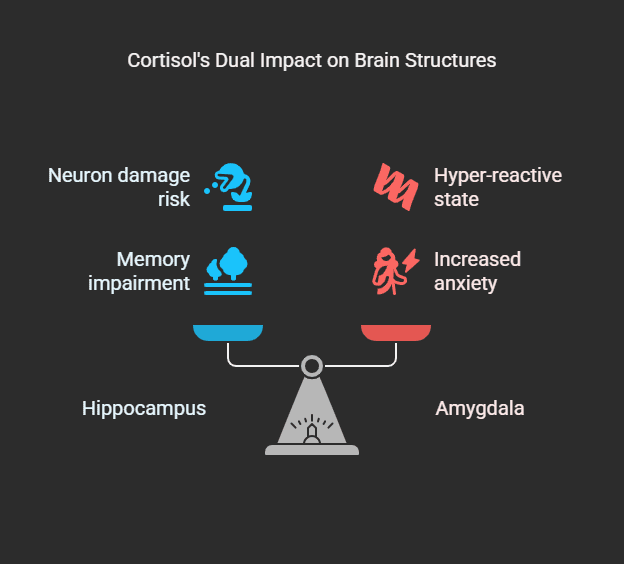

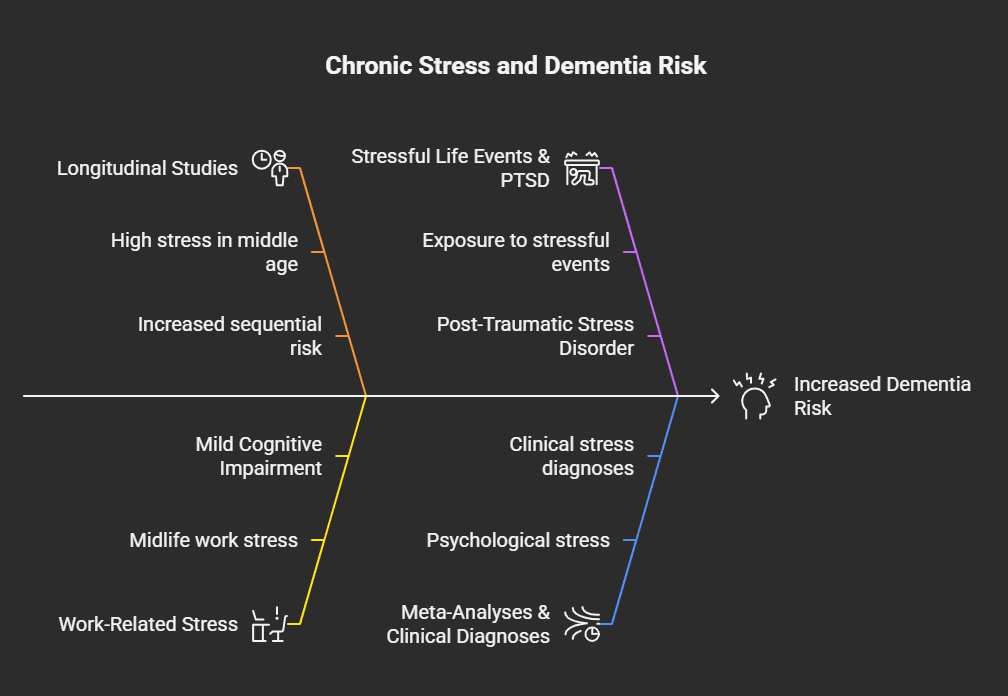

4. Stress Reduction: Exercise is an excellent stress buster. It normalizes the body’s stress response system (the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal or HPA axis) and reduces cortisol levels, the major stress hormone. Chronic stress has been shown to shrink the hippocampus (important for memory) and disrupt prefrontal cortex function (critical for decision-making), so reducing stress through exercise has great neuroprotective advantages.

These processes interact with one another, developing a situation within the brain that is beneficial to growth, adjustment, and highest functioning. Exercise isn’t simply strengthening your heart; it’s refining the control center of your entire organism.

Aerobic Exercise: The Cardio Champion for Cognitive Enhancement

When most individuals think of “exercise for brain health,” aerobic exercises tend to spring to mind first, and there’s a reason for that. Exercises such as running, swimming, cycling, brisk walking, dancing – anything that raises your heart rate and maintains it for an extended amount of time – are especially effective brain enhancers.

Effect on Memory:

Aerobic exercise significantly impacts the hippocampus, a brain area responsible for learning and the creation of memory, especially spatial memory and transferring short-term memory to long-term memory. This is how

- BDNF Spurt: Aerobic exercise pumps up BDNF levels profoundly, particularly in the hippocampus. This surge enhances neurogenesis (more later!) and strengthens synaptic links, facilitating easier creation and recall of memories. Aerobic exercise has been demonstrated to grow the hippocampus itself, reversing age-related shrinkage that so commonly leads to declining memory.

- Enhanced Blood Flow: The greater oxygen and nutrient supply directly supports the function and resilience of hippocampal cells.

- Neurotransmitter Balance: The activation of acetylcholine, dopamine, and norepinephrine through aerobic exercise also contributes to memory encoding and retrieval.

Imagine your hippocampus as a library of your memories. Aerobic exercise creates more neurons (neurogenesis), makes the old ones stronger (synaptic plasticity), and enhances the librarian’s performance (neurotransmitter function).

Impact on Focus and Attention:

Getting a little fuzzy mentally? A run or brisk walk could be the ticket. Aerobic exercise improves executive functions, which are overseen mostly by the prefrontal cortex. These include:

- Planning and organization

- Working memory (keeping information in mind to play around with it)

- Attention control and focus

- Inhibitory control (staying on track despite distractions)

- Cognitive flexibility (alternating between tasks)

How does cardio help?

- Increased Prefrontal Cortex Activity: Aerobic exercise increases blood flow and activity in this vital area.

- Dopamine and Norepinephrine Release: These neurotransmitters are critical to sustain alertness, attention, and goal-directed behavior.

- Improved Efficiency of Neural Networks: Regular aerobic exercise appears to make the communication networks between various brain regions responsible for attention and control more efficient.

Impact on Neurogenesis:

This is where aerobic exercise comes into its own.

Although neurogenesis persists throughout life, it can happen most easily within the hippocampus

Cardiovascular exercise is the most intensively reported behaviourally evoked stimulus to induce hippocampal neurogenesis in adults. BDNF increased dramatically following cardio, directly impelling stem cells of the hippocampus to convert to new neurons. New neurons make their way into established hippocampal networks and improve the learning potential, as well as memory versatility. It’s constructing a ‘younger’ brain, neuron by neuron.

Strength Training: Developing Brainpower Along with Building Muscle.

For many years, the mental benefits of exercise were mostly credited to aerobic exercise. But more and more studies are now demonstrating that strength training (or resistance training) – weight lifting, resistance band work, or bodyweight exercises such as push-ups and squats – also has distinctive and substantial benefits for your brain.

Impact on Memory and Executive Function:

Although perhaps not as strongly stimulating BDNF as high-intensity aerobic exercise, strength training accomplishes its magic through slightly different, yet complementary, mechanisms:

- IGF-1 Boost: Resistance exercise particularly well elevates levels of Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1). As noted above, IGF-1 traverses the blood-brain barrier and works together with BDNF to promote neuronal health and plasticity and thereby potentially enhance memory and cognitive function.

- Myokines: Muscles also behave like endocrine organs under strength training, secreting signalling molecules known as myokines (e.g., irisin, cathepsin B). Certain myokines can penetrate the brain and affect cognitive processes, such as memory and possibly neurogenesis, although studies are in progress.

- Better Glucose Metabolism: Strength training makes your body (and brain) more sensitive to insulin, so it can use glucose better. Better glucose metabolism is associated with improved cognitive function and reduced risk of dementia.

- Improved Executive Functions: Research indicates that strength training can enhance executive functions, perhaps by improving functional connectivity within brain networks supporting attention and cognitive control. The concentration demanded by lifts, planning exercise regimens, and monitoring progress may be part of the reason.

Preventing Cognitive Decline:

Strength training appears to hold special promise for maintaining cognitive function as we grow older:

- Maintaining Brain Volume: According to some research, resistance exercise will help retain, and possibly add volume, to certain parts of the brain, potentially offsetting age-related shrinking.

- Cutting Back White Matter Lesions: White matter lesions correlate with mental decline. Strength training will cut back their growth.

- Better Functional Independence: Since resistance training serves to preserve strength and muscle mass, it encourages older adults to remain active, which indirectly translates to cognitive advantage.

Aerobic exercise may be the MVP for hippocampal neurogenesis, but strength training is an equally effective add-on strategy with the ability to enhance executive functioning, metabolic status favoring the brain, as well as have potentially distinct neuroprotective impacts via factors arising from muscle tissue. A healthy regimen that blends both is probable the best overall strategy.

Yoga and Mind-Body Practices: Finding Focus, Calm, and Clarity

Yoga, Tai Chi, and Qigong combine physical postures, breathing techniques, and meditation or mindfulness elements. These practices offer a unique blend of physical and mental training with distinct benefits for the brain.

Impact on Focus, Attention, and Interoception:

Mind-body practices train your ability to pay attention, both to external stimuli and internal sensations (interoception).

- Improved Attention Control: The attention needed to maintain postures, coordinate breath with movement, and meditate strengthens the brain’s attention networks. fMRI studies have demonstrated changes in brain areas involved in attention (such as the prefrontal cortex) in frequent yoga practitioners.

- Enhanced Interoception: Mindfulness and yoga develop sensitivity to subtle body cues – your heartbeat, breath, muscle tension. Increased interoceptive awareness is associated with improved emotional regulation and decision-making.

- Mindfulness and Working Memory: The mindfulness aspect, being present without judgment, can decrease mental clutter and enhance working memory capacity.

Effect on Stress Reduction and Mood:

This is one of the key strengths of mind-body practices.

- Parasympathetic Activation: Techniques for deep breathing that are typical of yoga (pranayama) trigger the parasympathetic nervous system – the body’s “rest and digest” system. This opposes the “fight or flight” response of the sympathetic nervous system, decreasing heart rate, blood pressure, and cortisol.

- GABA Boost: Certain research indicates that yoga is able to elevate levels of GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid), a neuroinhibiting neurotransmitter responsible for soothing nervous system activity. Low GABA levels are related to anxiety and mood disorders.

- Amygdala Regulation: Meditation techniques, commonly included within yoga, have been found to decrease activity and even grey matter volume in the amygdala, the center of fear within the brain, resulting in lowered reactivity towards stressors.

Effect on Memory

Although direct neurogenesis impacts may be less significant than with intense cardio, yoga positively affects memory indirectly

- Stress Reduction: By reducing cortisol, yoga shields the hippocampus from the harmful impacts of chronic stress.

- Improved Focus: Increased attention and decreased mental clutter naturally enhance memory encoding and retrieval processes.

- Structural Changes: Long-term practice of yoga has been linked to higher grey matter volume in areas of the brain that are implicated in learning, memory, and emotional regulation.

Yoga and other mindfulness practices rewire the brain by increasing self-awareness, refining emotional regulation, soothing the nervous system, and improving focus, building a mental landscape that supports clarity and resilience of mind.

How Physical Exercise Rewires Your Brain: The Science of Neurogenesis and Neuroplasticity

Let’s focus on the two fundamental concepts that describe how physical exercise reshapes your brain: neurogenesis and neuroplasticity.

Neurogenesis: Creating New Brain Cells

As stated, neurogenesis is the creation of new neurons. We used to think that we were born with every neuron we’d ever possess. We now realize that this is not the case, especially in certain areas of the brain such as the hippocampus (memory) and the olfactory bulb (smell). Aerobic exercise, in particular, is a strong inducer of hippocampal neurogenesis.

- The Process: Exercise raises BDNF. BDNF instructs neural stem cells in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus to divide and mature into functional new neurons.

- Integration: These new neurons move and integrate into pre-existing neural circuits. This is not only about quantity; this is about increasing the capacity of the network. New neurons are believed to be highly excitable and plastic and play an important role in learning new things and differentiating between similar things (pattern separation).

- Survival: Not all the new neurons live. Whether or not they get used – doing mentally stimulating tasks and exercise allows these new cells to remain and play a role in the long term.

Exercise provides the potential for greater learning and memory by offering up the building materials (new neurons) and supportive conditions (BDNF, blood flow).

Neuroplasticity: Redesigning Connections

Neuroplasticity is the general concept that includes the capacity of the brain to change its structure and function in relation to experience. It occurs continually, but exercise significantly enhances several types of plasticity:

Synaptic Plasticity: This is a term for modifications in the strength of synapses between cells. Exercise promotes processes such as Long-Term Potentiation (LTP), which enhances synapses and enables more efficient communication between cells. This is essential for learning and memory. Consider it to be paving and expanding the highways between brain locations that regularly have a lot of traffic. BDNF comes into play here as well.

Structural Plasticity: Exercise can cause visible changes in brain structure, including:

- Greater volume of grey matter (neuron cell bodies, dendrites, synapses) in regions like the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex.

- Enhanced white matter integrity (myelinated nerve fibres that link different brain areas), which results in speedier and more effective communication between brain networks.

- Higher density of dendritic spines (dendrites are neuron branches that receive inputs). More spines, more possible connections.

Functional Plasticity: The brain can reassign functions from the damaged region to an undamaged region or reorganize the way it engages various regions to accomplish a task more effectively. Exercise appears to enhance this adaptive function.

Basically, exercise makes your brain more efficient, resilient, and flexible. Exercise strengthens valuable connections, weakens poor ones, promotes new pathway growth, and even restructures the physical landscape of brain areas responsible for thinking, learning, and emotion. This continuous rebuilding is the quintessence of how physical exercise rewires your brain

Practical Tips: Incorporating Brain-Boosting Exercise into Your Life

.Learning the amazing brain advantages is inspiring, but how do you take that and turn it into action?

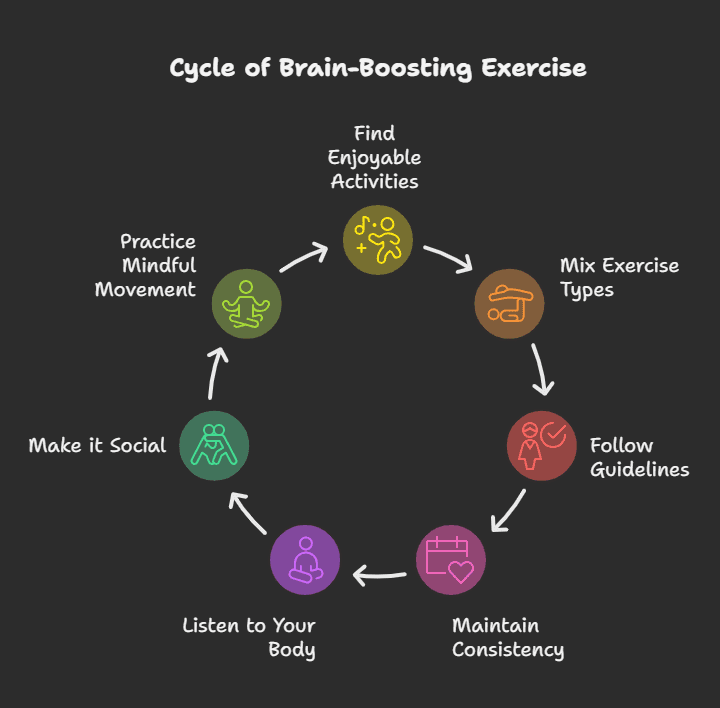

- Find What You Enjoy: You’re more apt to stick with things you really like. Try on various activities – dancing, hiking, team sports, weightlifting, swimming, yoga classes, and fast-paced walking with a podcast.

- Mix Up Different Types: Try to mix aerobic, strength, and mind-body exercises for the widest variety of brain advantages. For instance, 2-3 days of cardio, 2 strength training days, and 1-2 sessions of yoga or stretching per week.

- Follow Guidelines (But Start Where You Are): General guidelines usually recommend 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity (such as brisk walking) or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity (such as running) per week, with muscle-strengthening activities two times a week. But something is better than nothing. Begin slowly and increase duration and intensity over time.

- Consistency is the Key: Daily exercise yields the greatest long-term brain advantages. Prioritize consistency over occasional intense bursts. Short, regular sessions also accumulate.

- Listen to Your Body: Prevent overtraining that can lead to increased stress and inflammation. Leave room for rest days and recovery.

- Make it Social: Working out with friends or taking a class can increase motivation and provide a social connection factor, which is also good for brain health.

- Mindful Movement: Tune into your body and breath while exercising, even with cardio or strength training. This increases the mind-body connection.

Conclusion: Move Your Body, Master Your Mind

TThe evidence is undeniable and convincing: exercise is not just good for your body; it’s also good for your mind. Understanding how physical activity affects your brain changes the way we think about exercise from a chore to an investment in our mental sharpness, emotional strength, and brain health over time.

Movement changes the structure and function of your brain in a good way. For example, aerobic exercise can help you remember things better, strength training can help you concentrate better, and yoga can help you relax and think more clearly. Exercise improves the way we think, learn, and feel by increasing blood flow, releasing good neurochemicals like BDNF, reducing inflammation, and promoting neuroplasticity.

When you put on your running shoes, pick up a weight, or step onto your yoga mat, remember that you’re doing more than just working out your muscles. You are taking part in an act that will change your brain in a big way. You’re making your brain stronger, sharper, and tougher with each workout. Don’t just look at the biceps; recognize movement as the powerful brain tool it is. Your future self will be grateful..